bibliometric mapping

OUR RESEARCH PROJECT

Before attempting to advance the field of data and AI ethics research, JUST AI had to understand what work had already been done and was needed. We used bibliometric analysis to map the relevant communities and sets of connections within the UK. This research project sought to answer the following questions:

-

What is data and AI ethics research?

-

Who conducts it?

-

How can people find out about this research?

-

How can they find their own position in this community?

-

How can we create inclusive dynamics and foreground marginal voices and emergent practices?

In doing so, we hoped to intervene in data and AI ethics work by engaging different voices and approaches after understanding where they do or don’t appear in research.

OUR PROCESS

By 2019, there was an exponential increase in language evoking data and AI ethics in published academic research. Taking inspiration from studies of research networks and invisible colleges that have extended back in social science over the last hundred years, we initially approached our work by identifying the dominant narratives that appeared in a burgeoning field.

We first attempted to map the field by scraping data about individuals and their affiliations from research profiles on university websites to conduct social network analysis. This was very labour-intensive and organised around institutional affiliation. The results gave a glimpse into the political economy of data and AI ethics research because of the powerful institutions that commanded influence as well as resources in the field. While valuable insight into how people and power were consolidated, we still didn’t have a sense of how ideas were related more broadly.

Network visualization institutions participating and related in data and AI ethics research generated by web scrapping

We turned to an automated literature mapping led by Imre Bard to search for terms that we thought would indicate data and AI ethics (big data, machine learning, moral, etc) in six large databases (Clarivate Web of Science, ACM, ArXiv, SSRN, IEEE, SpringerLink). Admittedly, this was a narrow definition of ethical work because we only sourced people who explicitly said they were doing data and AI ethics research. While this gave just one orientation we thought it was an important one because it reflected those who believed they were doing work that was “legitimate” in this rapidly emerging field.

We clustered the data we collected with various paramaters and see what emerged. When arranged by institutional collaboration we found Oxford and Cambridge dominate the UK’s canonical data and AI ethics research space but also identified smaller universities with significant work such as Cardiff, New Castle, and Sheffield. International influences include the United States, Netherlands, and Switzerland. These initial maps again showed the consolidation of existing influence, that historically dominant institutions are able to define research areas, and how the framing of what constitutes data and AI ethics research is likely constructed from a western perspective. We also saw a centralization of particular author perspectives but acknowledged that this might have been because of how research is cited and that our search terms were likely to turn up citations and recitations. A gendered analysis of the biographies of prominent authors in this network produced a large representation of male-identified people. While there are many interpretations to make from the bibliometric analysis, the narrative they were telling was becoming clear.

Network visualization of bibliometric analysis filtered by institutional collaboration

Download our essay on “Mapping AI and Data Ethics”

OUR BREAKTHROUGH

We began to think of how to explore representational methods in a more critical or interventionist way. Centrality is a metaphor and artefact of bibliometric analysis, particularly of the computational assumptions that are made through the parsing of data and the analytical or visual choices. Network analysis methods reiterate these narratives about centrality because showing who is at the center reinforces that certain perspectives are important. Instead of continuing to use these methods to identify an already dominant narrative, we wanted them to identify and organise other kinds of connections.

Using the same networks we had mapped, we identified specific references to philosophical traditions to pull out the epistemological assumptions people were making when they wrote about data and AI ethics. This was a way to start looking at networks differently and what we could do with network methods in order to make visible what is less seen.

We broke free of the canonical definition of data and AI ethics by incorporating the keyword “data justice”. When we did, we found a few individuals connecting two considerations of morally-driven work. In thinking about who is connecting the dominant narrative to less dominant ones and how JUST AI could make similar connections, our project transitioned from describing networks to creating them.

Up until this moment, JUST AI had been defining a problem in data and AI ethics research, but now there was potential to change how that research is performed by linking together different kinds of discussions or highlighting areas in data and AI research that were not being treated as ethical issues.

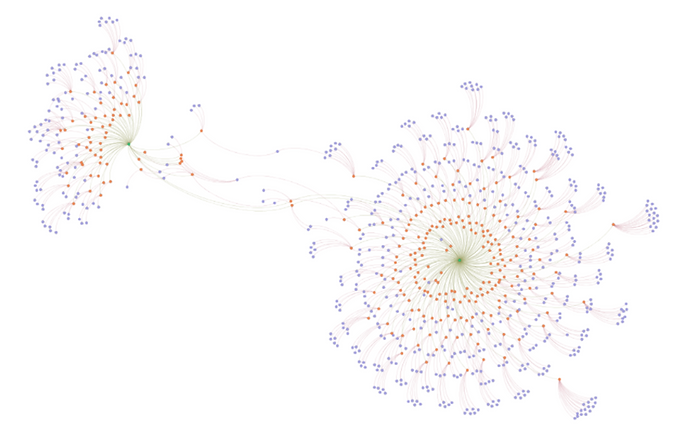

Network visualization of articles (orange) and authors (purple) addressing ‘data justice’ on the left and justice-related work within AI ethics on the right. The few dots connecting the two clusters represent the few individuals connecting the topics.

Download our essay on “Networking with Care”

RESOURCE LIST

ESSAYS

PAGES